How Stellaris has taken on new life over its six-year strategy journey

We chat to director Stephen Muray about the evolution of Paradox's 4X space epic and its sci-fi inspirations

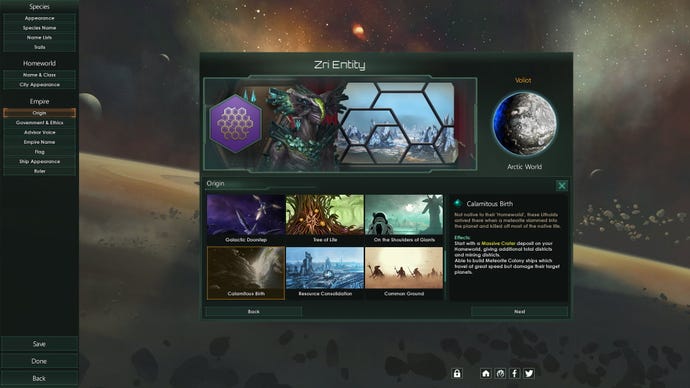

Galactic alliances aren’t built in a day, a month or even a year, to warp a comfortingly familiar phrase from 90s telly. Interplanetary 4X Stellaris has been evolving for more than six years now, having first released on May 9th 2016. Unusually, I remember exactly when I bought the game, because it was in the days just before my partner and I welcomed our first child. Being a ginormous sci-fi nerd, I enthusiastically downloaded it thinking I’d have all the space-time in the universe to invest in building my own interstellar superpower.

I did dip my toes in back then, and have many, many times since, but rather naively didn’t foresee the inevitable. The structure of my life altered dramatically with the arrival of our baby. It didn’t stop there either, and still hasn’t, taking on some unfamiliar but just about recognisable form every few months. I suspect the developers of Stellaris had a similar feeling following the game’s release into the wider universe, like Kubrick’s giant cosmic infant at the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey. I know I’ve felt like my furniture’s been rearranged whenever I’ve started a new game of Stellaris with a different civilisation over the intervening years.

"The biggest constant in Stellaris is change," current game director Stephen Muray says, reassuring me that I’m not overstretching my child-rearing analogy. Muray is Stellaris’ fourth director, taking over after Daniel Moregård's three-year tenure ended earlier this year. "We’ve learned a lot from when we took our first steps out into the 4X world to where we are today. We’ve been unafraid to make major changes, and even retract changes when we’ve made missteps. Stellaris is a very different game from launch day.

"The various economic changes have had major impact, of course, as have the addition of countless new features,” he continues. "But I think the biggest overall change… is that we shifted a bit from the basic 4X model we started with and embraced being a game about the exploration of possibilities and building your own narratives."

Indeed, Paradox Development Studio have consistently updated the game with new features alongside the hefty additions included in its paid DLC. Muray explains that he oversees what goes into the free updates and what features are kept for the expansions, with the basic game systems forming the core of any updates, and the "meat" reserved for the DLC’s second course.

"The biggest reason for this is because it lets us build upon that content later without requiring multiple DLCs to access it," he says. "For example, the archaeology system came out alongside Ancient Relics, and most of the content for it was in Ancient Relics itself, but we were able to add the Hauer system in a free update without any problems since the system itself was free.

"Soft locks aren’t something that will prevent us from producing content though," Muray adds. "If someone on the team has a great idea for content for Hive Minds, Machine Intelligences, or Megacorps, I don’t want to block the idea just because it’ll also require Utopia, Synthetic Dawn, or Megacorp to access."

The most recent major update, Cepheus, and latest expansion, Overlord, arrived to coincide with the game’s sixth anniversary in May. Stellaris is now on its 21st major patch, most of which have been named for famous sci-fi authors such as Ursula Le Guin and – hat tip – CJ Cherryh. The game’s also received ten significant feature-packed DLCs. They’ve incorporated everything from Star Trek-style federations to fallen empires like Babylon 5’s Shadows and Vorlon, and even AI rebellions reminiscent of Mass Effect’s artificial Geth uprising.

While Stellaris started out as a relatively blank slate compared to its 2022 iteration, it’s grown through inspirations drawn from a multitude of earlier examples of the speculative fiction genre that permeate pop culture, and have influenced its development team. Muray tells me that the breadth of science fiction is what drew him to Stellaris.

"Everything in the sci-fi genre is within our purview," he says. "There are so many possibilities to explore and stories to tell, it’s that vastness and freedom that appeals to me. I love the tagline 'the galaxy is vast and full of wonders' and how it guides everything we do."

I'll admit that I’m a particular fan of authors Alastair Reynolds and Larry Niven, and ask who he and the team are fond of. "I’ve recently been working my way through rereading Banks’ Culture series," he says. "Corey and Asimov take up quite a bit of space on my e-reader as well."

"Without treading into 'promises' territory, I want the sandbox to expand to include more emergent stories."

The rest of the team namecheck an array of wildly dissimilar authors from the past century – Vernor Vinge, William Gibson, Alfred Bester, Michael Moorcock, Stephen Baxter, Liu Cixin, Adrian Tchaikovsky – so I’m not surprised that Stellaris seems to draw on such a range of influences. I ask what the team would most like to work into the game in the future and, again unsurprisingly, Muray provides a clear goal of deepening Stellaris’ compelling storytelling.

"Without treading into 'promises' territory," he says, "I want the sandbox to expand to include more emergent stories. Whether that be through more detailed interactions with your factions, political rap-battles in the Galactic Community, changes to how leaders work, exploring the rise and fall of empires in new ways, or reworking how you deal with pre-FTL civilizations… I can’t say, but I think we’ve done our job best when you can’t get to sleep just yet because you want to discover what happens next."

As the befuddled and time-strapped parent of an increasingly complex and interesting child, I greatly appreciate Muray’s other aim for Stellaris’ future. "I’d also very much like us to make the game more accessible to new and existing players," he adds, "from improving automation to reduce the mental burden from micromanagement to streamlining things that are currently just a bit confusing."

Speaking of complexity, Muray tells me that the most obvious aspect of sci-fi that the team haven’t yet found a way to work into Stellaris is Trek-like cloaking technology, that classic sneaky Klingon and Romulan tactical boon. They think it’d be too tricky to achieve cloaking in a satisfying way without it affecting a lot of the game’s other systems. That said, while some things don’t work out straight away, they do sometimes end up being incorporated into other updates further down the road.

One example Muray offers is an 'intel ledger' that the team hoped to include in last year’s Nemesis update. "Generally when something balloons in scope to infeasibility, it’s tied to being part of a complicated UI," he says. "Those ideas didn’t get completely lost forever though, parts of the original idea were used in the Espionage tab and some parts morphed into the Agreements summary in Overlord."

Over years of regular updates and expansions, piling changes and extra features onto an already systems-orientated game such as Stellaris can cause some issues. Muray, his predecessors and the wider development team have coped admirably with this process. They seem confident that there’s plenty of opportunity to expand Stellaris yet further.

"We have a pretty solid base to build on at this point. While there are still some systems that could use a bit of reconfiguring or improvement, there’s a lot that we can do with what we have," Muray says. He explains that the Custodians Initiative set up by Paradox to polish the game with balance changes, stability tweaks and quality of life improvements last year has helped Stellaris enormously, "fixing technical debt that had piled up over the years."

"It took a while for Stellaris to 'find itself', to carve out the niche that defines who we are and what the stories we want to help tell are."

"As for limitations," Muray adds, "when working on an older project you have a lot of legacy to work with. Or around." Cheekily, I enquire how a sequel might differentiate itself from the current game and the other grand strategies that Paradox are known for. "It took a while for Stellaris to 'find itself'," he says, "to carve out the niche that defines who we are and what the stories we want to help tell are.

"Theoretically, a sequel would start with a leg up and be able to build upon the starting point we provide them," Muray goes on to explain, "but they’d have the advantage of being able to plan for some of the systems we’ve changed from the start, and consider how they in turn would want to make them better." Although I’d welcome a Stellaris 2 if one were to ever arrive, it definitely doesn’t seem like a new game would be needed anytime soon.

The devs at Paradox are ramping up right now for the release of Stellaris' next major update, 3.5 Fornax. As noted in their dev diaries, they're still continuing to push out smaller changes too, such as the recent inclusion of an even easier difficulty setting than Cadet, dubbed Civilian, and some more granular choices for mid and late game difficulty scaling.

Just for funsies, I wrap up our chat by asking Muray what humans have on their side that a galaxy full of intelligent space-faring funguses and autocratic robots don’t. "Craft beer and the will to try the impossible," he says. "Sometimes these are closely linked." I’ll have to remember to pass that wisdom on to my daughter, in case she ever encounters an alien civilisation that worships multi-dimensional pretzels.

Stellaris is available on Steam, GOG and Game Pass for £35 / €40 / $40, and continues to be one of the best strategy games and best space games you can play on PC today, especially with its multitude of mods.